Memories of a Third Assistant Director

Soon after joining The Saint as a fresh-faced 19-year-old kid straight out of school, Pat Kelly, the tough old Irish First Assistant Director, took one look at me and told me something I’ve never forgotten. “I never want to f****ng see you”, he said, “but when I take one step backwards I want to tread on you.” It’s probably the best job description for a third assistant director one could ever get.

If the First Assistant Director is like an army sergeant major, running the set, the ‘Third’ is the ‘First’s’ assistant, staying out of the way but always trying to second-guess the First by making sure everything’s prepared a split second before the director needs it. Being a Third in those days, in the final years of the old British studio system, was the most incredible training for a young kid. The directors on The Saint were the giants of British filmmaking, men like Roy Ward Baker, Leslie Norman, John Gilling and Bob Tronson. Some—especially Leslie Norman—had made their reputation back in the old Ealing Studios days, and saw series like The Saint, Gideon’s Way and The Avengers as a pleasant way to end their careers. Others directed episodes for these TV series in between movies, but all had incredible reputations. Watching them, trying to second guess what they were doing so ‘the floor’ was never held up, was like a graduate degree in film.

Some of the Firsts were as legendary as the directors, especially Pat Kelly. This was a time when being a top First Assistant Director was the height of a particular career path in movies, like being the ‘Sergeant Major of the Army’. Pat was in his late 40s then, a tough little scrapper of a man who could intimidate the biggest stars and the most successful directors with just a look.

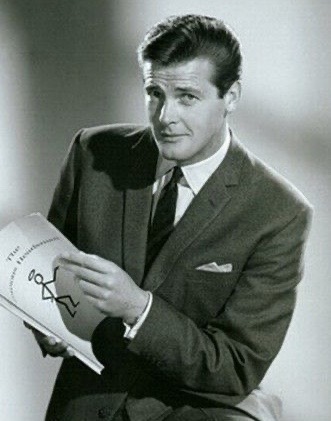

Of course a Third’s job involves more than calling actors when needed. I served at the whim of the First, helping direct extras (directing extras is another job done by the First), getting him tea and bacon rolls and just relaying instructions and doing whatever else was needed to keep the shooting on schedule. But calling actors on stage (especially Roger Moore) always got me yelled at more than anything else. Roger would frequently be ‘holding court’ with visitors in his dressing room and hated to be interrupted. My job was to get him down on set that split second before the director needed him. His attitude (like every other star from the beginning of the movies down to the present) was to spend as little time on set as possible. I’d knock on his door. He’d say he was on his way. I’d return to set. Roger wouldn’t come down. The First would yell at me. I’d knock on Roger’s dressing-room door again. He’d then yell at me for badgering him or, even worse, come on my first call and find I’d called him too early so yell at me for that.

You get the picture; the Third gets yelled at by everyone. It’s something producers created long ago to relieve the tensions always present on a film set. You can hear them saying: “Why don’t we create a position for everyone to yell at to let off steam.” And so the Third was born. As a Third, you long for a promotion to Second, and finally First, so you can yell at your own Third. Thirds develop a thick skin and learn that the best way not to get yelled at is to really know what’s going on every moment on set.

But there were pleasures, and one of the greatest was getting to know the many beautiful young actresses who guest-starred in the various episodes. As anyone who has watched The Saint knows, Simon Templar was always helping out damsels in distress. While some of these young actresses were well known, most were early in their careers, cast as much for beauty as their acting ability (although many went on to become major actresses in British film and theater). It was the Third’s job to make sure they knew their call and we were expected to be at the studios with them at 7.00AM to ensure they were through make-up and wardrobe in time to be ready on set at 8.30AM.

After I bought a car—a very unreliable old ‘banger’—I’d often drive them to the studios in the morning. Many a pre-dawn morning I’d park outside some house in Hampstead or Belsize Park or Notting Hill Gate, waiting for some gorgeous creature to emerge; except not even the most beautiful actress in the world is gorgeous at 6.15AM on a winter morning with no make-up and her hair in a tangle. Suzan Farmer, Annette Andre, Ann Lynn, Jennie Linden, Jane Merrow, Viviane Ventura, Penelope Horner, Quinn O’Hara, all these young actresses made getting up so early in the morning a real pleasure. I was a shy kid. I’d been closeted in a series of ‘boys only’ boarding schools most of my life and barely knew how to talk to girls without blushing. These young actresses were kind and friendly and interested. Even after all these years, I’m still grateful to them.

Roger Moore as Simon Templar(The Saint)

I really liked Roger Moore, everyone did. While you didn’t want to feel the force of his temper and you tried to avoid being the focus of his practical jokes, he was always gracious to people on the set, even unimportant Thirds. It’s always been my measure of a star how they treat people to whom they don’t have to be nice. Roger did something incredibly special for me. It was October 12, 1966 and my 21st birthday. I’d made a point of not mentioning it around the studio—I think I was embarrassed—but Roger found out somehow. It was during an episode he was directing and normally the shooting day went on until 5.50PM. But at 4.30 he called a wrap. The prop guys wheeled a trolley onto the set full of champagne. Roger then announced “it’s Leo’s 21st birthday and we’re going to celebrate it properly.” You don’t forget something like that.

I mentioned it’s the Third’s job to help the First direct extras in background action. Crowd artists were—and may still be, for all I know—a breed unto themselves. They had their own union and their own social hierarchy. Many made being an ‘extra’ a full-time career, especially those with their own special dress, able to hold their own in scenes about high society. The power and influence you wielded in this hierarchy depended on your relationships with certain very powerful Firsts (and Seconds, the people who booked the extras). If you had sufficient influence to guarantee work for others, you had real power. The strategy was always to try and get called back the following day, or be given ‘special action’, where the First would give you something specific to do in the foreground of a shot. You got paid more for that. And if you got to speak a line, that was golden. Everyone connived to get more than the basic extra pay, and much was for sale.

When I was still new on the Saint, the First sent me up to the dressing room of a very sexy crowd artist who’d been given a small speaking part. I knocked on the door and told her she was needed on set. A husky voice invited me in. She lay, stark naked on the couch, arms open in invitation. I’ve already mentioned I was 19 and very shy. I went bright red and fled. As I got back on stage, stammering that I hadn’t been able to fetch her down, the whole crew burst out laughing. I’d been set up.

Leo Eaton worked as an assistant director on a number of British TV series between 1964 and 1967, including THE SAINT, GIDEON’S WAY and THE BARON.

In the strange twilight world of crowd extras, an unscrupulous First or Second (the majority weren’t) did well with kickbacks, sex and other incentives. Thirds were usually too low in the pecking order to count but crowd artists would still go out of their way to build relationships. Sooner or later you’d become a Second and then you’d have the power to help them directly.

There were definite connections between some of the extras and the London underworld. It was accepted that if you wanted someone roughed up, you could arrange it through particular crowd artists. Yet even the toughest of them were intensely loyal to anyone they knew from the studios. An actor I knew on one Saint episode was being threatened by a group of toughs operating one of the West End strip clubs of the time. A group of crowd artists made sure he was protected and succeeded in ‘discouraging’ the gangsters from causing further trouble.

While the majority of extras were ‘legit’, the extra business certainly had its seamy side during this period. Sometimes word would come down from front office that important people (we assumed financial backers) were arriving from the US and needed companionship. There were girls on the extra lists happy to oblige since it was understood this guaranteed call-backs whenever extras were needed.