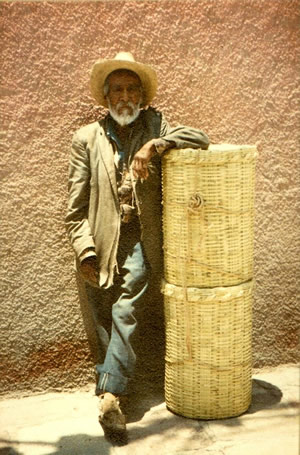

Siesta Hour in San Miguel (1969)

Siesta Hour in San Miguel (1969)

The cobbled streets dream in the midday sun. It is siesta hour and the entire town is as lazy as the two Indians who are asleep under their sombreros outside a cantina. The sun-baked houses are drowsy, filled with the listless sounds of noon; a transistor radio playing somewhere in the distance, the clink of bottles, the slow shuffle of an old man and his burro as they go from door to door, offering their load of wood to any who answer their call.

Beneath the arches of Los Dragones it is cool and dark, a stark contrast to the washed-out brilliance of the street outside. Antonia ferries bottles of Dos Equis beer from the gloom at the back of the bar to the front table that looks out onto the jardine. Here the artists and writers sit, watching the day slip lazily into afternoon. It is a constantly changing pattern, some drifting off, others coming to join the group at the front table, settling into the chairs of those who have just left. Faces change but the group and the conversation remains. Hour by hour, day by day, week by week, the artists and writers sit and talk in Los Dragones. It is our place and the town knows us and recognizes our claim. It is only the occasional tourist who tries to stake a claim to the front table. He never stays long; the writers and artists protect their territory.

The conversation falters and then picks up, turning to the latest painting, the latest book. One writer is waiting for a check from his publisher; an artist is having trouble with his latest canvas. The words rise and fall, the faces change but the conversation has its own continuity. Sit for long enough at the front table of Los Dragones and the whole world will pass in front of you.

Siesta hour settles on the group like a heavy cloud. Conversation slows and then dies, thoughts listless and heavy. Outside a policeman clumps slowly by on his way back to the police-station next door. He clutches a melting ice-cream cone in his grimy hand. His blue uniform is dusty and frayed at the edges, his boots are cracked and worn, his revolver is worn self-consciously at the hip. He passes Osso, the great dog that belongs to Los Dragones, asleep in the middle of the road. The world could come to an end and Osso would sleep on unconcerned. He blocks traffic and cars drive carefully around him. The policeman prods him gently with his boot. Osso opens one eye and looks up briefly, then yawns and goes back to sleep. The policeman passes on, reddening at the comments of his friends on duty outside the entrance to the town jail.

The iced beer bottles are sweating in the heat, beads of moisture trickling down onto the table. Listlessly one of the artists draws damp circles with his finger on the cracked wooden surface. The front face of San Miguel’s main church, the Paroquia, shimmers in the heat, a façade of pink stone copied from a picture postcard of Chartres. The architect was an Indian and knew no technique but he knew what he wanted. He’d seen Chartres in paintings and photographs. He drew an outline with a stick in the dust and the building rose like a fairyland castle, a pink wedding-cake of Gothic towers and stuccoed balconies.

Leo Eaton lived in San Miguel d’Allende from 1969 to 1970 and again in 1972. It’s where he met his wife and wrote his first book.

At the front table, flies buzz around the pools of spilled beer. Outside in the jardine old men snooze on the benches under the trees. Even the shoe-shine boys have left their posts. During siesta hour the whole world stops and draws breath. Glasses are empty on the front table and Antonia brings fresh bottles from the back. All sounds have a muted quality; the cries of small boys playing under the arches on the other side of the jardine, the clatter of bottles. Antonia is putting another case of beer on ice at the back of the bar, in the old ice-box that shares pride of place with the suits of armor and the owner’s collection of antique pistols.

The group at the front table sits lost in its own thoughts; talking is too much effort. A bus full of tourists pulls into the jardine and its passengers get off, loud and out of tune with the town as they click their cameras and call to each other in shrill tones. Their voices are harsh; they shut out the peace like an enemy. The writers and artists look at each other in disgust. They sit apart from the activity outside, watching and discussing and sometimes using what they see as the starting point for a drawing or short story.

The hour trickles past. The tourists return to their bus with appetites satisfied by a surfeit of churches and native color. Conversation returns to the front table, picking up where it left off twenty minutes earlier. Osso wakes and stretches slowly, mouth gaping in a cavernous yawn. Leisurely he gets to his feet and shambles into the gloom of Los Dragones, settling down again under the front table and going to sleep immediately. The shoe-shine boys return to their posts, eyes following every new arrival in the jardine with hopeful speculation. The siesta hour is past and the town begins to wake.

The hour trickles past. The tourists return to their bus with appetites satisfied by a surfeit of churches and native color. Conversation returns to the front table, picking up where it left off twenty minutes earlier. Osso wakes and stretches slowly, mouth gaping in a cavernous yawn. Leisurely he gets to his feet and shambles into the gloom of Los Dragones, settling down again under the front table and going to sleep immediately. The shoe-shine boys return to their posts, eyes following every new arrival in the jardine with hopeful speculation. The siesta hour is past and the town begins to wake.

But in the cool shadows of Los Dragones, the artists and writers go on sitting and watching. They are spectators of a world that ebbs and flows in the street outside. They are not native to this place, coming from America and England and Germany and so many other places to live the bohemian life in this beautiful Mexican hill-town. San Miguel was an art colony long before they established their claim on the front table of Los Dragones; it will be an art colony long after they are gone. And yet for now it is their time and their town. And perhaps, if they are lucky, some painting or story created here will bring this time and place back to life in a very different world many years from now for strangers who’ve never even heard of San Miguel. Can any artist ask for more?