We called him a primitive. We likened him to Gauguin or Rousseau. In most ways we were proud to think he was our friend and yet, in a much deeper way, we thought him a figure of fun, someone to laugh at in a tolerant fashion for his idiosyncrasies.

We called him a primitive. We likened him to Gauguin or Rousseau. In most ways we were proud to think he was our friend and yet, in a much deeper way, we thought him a figure of fun, someone to laugh at in a tolerant fashion for his idiosyncrasies.

Dan was tall and gaunt. His face, covered by a shock of black hair, was all angles and deep hollows. When on occasions I would arrive at his studio and catch him without his teeth, Dan would look almost exactly like the Frankenstein imitations he would sometimes do at parties when people had plied him with too much drink. I never really knew how old he was although he was probably in his middle forties. Dan was an oddity, even in a town so full of oddities as San Miguel.

When I first met Dan he lived in a house on the Calle Umeran. The street ran downhill from the jardine at a gentle rate until it passed the short steps that led to Dan’s door. Here the road plunged down precipitously to the hollow where the houses of the poorer Mexicans began. Dan lived right at the edge, on this borderline between wealth and poverty, the middle-class and the peasant. The windows of his house were always shuttered. I don’t think he ever had them open in all the time he lived there. The front step usually held several Mexican children, sitting and watching the passers-by in the street, waiting until Dan would invite them inside to pose for one of his innumerable drawings.

I first met Dan through Andrew Rogers, the English artist who had been responsible for my living in San Miguel. Andrew had a house right across the street from Dan and a kind of friendship had grown up between the two men. Dan was the exact opposite of Andrew, exuberant in his use of color where Andrew was controlled, dramatic in his use of line while Andrew planned every brush-stroke and charcoal mark. Andrew, a good deal younger than Dan, admired his work but could not think in Dan’s terms. Dan, standing in puzzlement before Andrew’s rigid and disciplined paintings, made no pretence of understanding. Yet the two artists admired and respected one another.

I first met Dan through Andrew Rogers, the English artist who had been responsible for my living in San Miguel. Andrew had a house right across the street from Dan and a kind of friendship had grown up between the two men. Dan was the exact opposite of Andrew, exuberant in his use of color where Andrew was controlled, dramatic in his use of line while Andrew planned every brush-stroke and charcoal mark. Andrew, a good deal younger than Dan, admired his work but could not think in Dan’s terms. Dan, standing in puzzlement before Andrew’s rigid and disciplined paintings, made no pretence of understanding. Yet the two artists admired and respected one another.

Dan Brennan ArtSoon after my arrival in San Miguel, Andrew had told me about Dan and I had viewed with interest the gloomy shuttered house that was almost touching distance across the street. At this time Dan was going through one of his hermit periods. Shut up in his house for weeks at a time, only emerging to visit one of the small back-street peasant restaurants where he ate, Dan would paint and draw, drawing his inspiration and his models from the people and countryside around him. Then when nobody had seen Dan for weeks, he would suddenly emerge to visit a friend. Starved of company and conversation, he would sit and drink coffee throughout an evening and a night, talking in a monologue about the work he was trying to do. Then at dawn he would return to barricade himself into his house once more.

It was on such an occasion when I was visiting Andrew that I met Dan for the first time. I don’t remember what we talked about; art, I expect, for no one spoke of much else in that company. However I do remember being totally fascinated by this lugubrious-looking man who looked as though he was about to die of starvation. Kirsten, Andrew’s wife, must have fed him. That was expected in those days. Then, later in the evening, Dan took us back across the road to look at his latest work. There in his dingy shuttered rooms I saw for the first time art that I have always considered unique and brilliant.

It was on such an occasion when I was visiting Andrew that I met Dan for the first time. I don’t remember what we talked about; art, I expect, for no one spoke of much else in that company. However I do remember being totally fascinated by this lugubrious-looking man who looked as though he was about to die of starvation. Kirsten, Andrew’s wife, must have fed him. That was expected in those days. Then, later in the evening, Dan took us back across the road to look at his latest work. There in his dingy shuttered rooms I saw for the first time art that I have always considered unique and brilliant.

Dan Brennan ArtThe rooms were empty. On the ground-floor just a mass of junk piled into one corner, a filthy lavatory, a kitchen with only one burner that hadn’t been cleaned in months. Rickety wooden stairs with no covering, two rooms upstairs empty except for the piles of junk on the floor; a dirty pallet bed in one corner, an easel, all the paraphernalia of paints and painting, and canvasses. There must have been dozens of them, hanging on every wall and stacked in every corner. I don’t think more than half the rooms had light, usually just one bare electric bulb hanging from the ceiling.

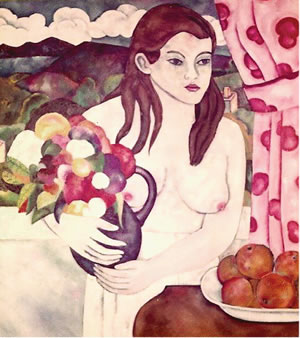

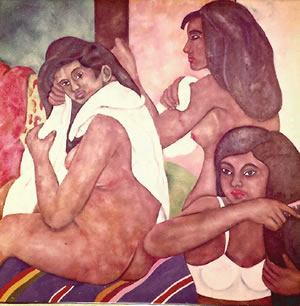

I stood and stared at Dan’s work, the best work he has ever done. It was the work of a true pure primitive of great talent. Portraits of Indian girls, children, still life’s, landscapes. All painted with an almost childlike exuberance, rich blazing colors burning out of the canvasses. All unframed, many covered in dust, and lit only by a single swinging electric bulb.

I got to know Dan quite well in the months that followed and I think that in a way we became friends, if it is ever possible to become friends with such a complex person.

Dan Brennan ArtThen I left San Miguel for almost a year. When I returned, Andrew had returned to Canada but Dan was still there, living in a different house now, further down in the peasant part of the town. It was as though more and more he was retreating from the artistic pretensions of the rest of the town.

Dan Brennan ArtThen I left San Miguel for almost a year. When I returned, Andrew had returned to Canada but Dan was still there, living in a different house now, further down in the peasant part of the town. It was as though more and more he was retreating from the artistic pretensions of the rest of the town.

Yet I found him changed too, different, more open and less of a recluse. Some years before, during one of his lean periods, Dan had completed a huge mural on the back wall of a restaurant, the Bodega. For a long time this had been the only visible sign of Dan around the town. Now, however, his paintings and drawings started showing up everywhere. A number of restaurants had them prominently displayed, returns for the free meals they had given him. Fellow artists bought them, often for a pittance, at a time when Dan desperately needed money to keep alive, pay his rent or go on a border trip. One of the galleries in town started accepting his work and sometimes a dealer from Kansas, Dan’s hometown, would send him a check for pictures that had been sold in the U.S.

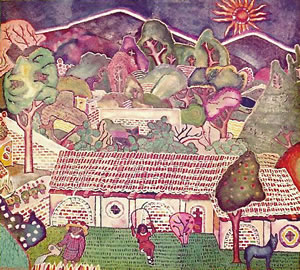

Dan Brennan ArtDan was different, more sociable. His work was beginning to change as well, the still life’s and portraits giving way to his new excursions into fantasy. These new paintings when they worked were perfect, a magical excursion into a child’s picture book. His new house echoed his changed mood. It was bright and open with two large airy rooms, painted white, and a big back patio with a tank for washing clothes. All the local children would come to take their baths in the tank and whenever I visited Dan the house was full of laughing half- naked Mexican children. The rooms were stacked with his paintings and he had great plans to paint a huge fantasy on the brick wall at the back of the patio, a fantasy of flowers and trees and animals and children.

Sometimes one of the peasant girls would be there, shy and timid as she sat for a drawing. I never was sure about Dan’s relationship with women although he once told me that the reason he liked the peasant girls was because they had such coarse large hands.

Dan was unique, an oddity, and his work was still growing day by day. Yet we all used Dan, usually without realizing it. We took his work for ridiculously low sums whenever he was so broke that he’d sell a painting in exchange for a square meal. We used him for his oddities. He was the ‘character’ that we liked to have at parties because he was different and amusing. A party was never complete without Dan getting drunk. Then he’d take out his teeth, put his black jacket on back to front and stagger around the room in one of his renowned ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ impressions, an impression I must admit to never having seen better done either before or since. In a strange way Dan seemed to play up to this new mood as if it was the only way he could relate with people. It was as if, having finally emerged into society and finding total acceptance in the role of the clown, he had decided to play the part to the utmost.

Dan was unique, an oddity, and his work was still growing day by day. Yet we all used Dan, usually without realizing it. We took his work for ridiculously low sums whenever he was so broke that he’d sell a painting in exchange for a square meal. We used him for his oddities. He was the ‘character’ that we liked to have at parties because he was different and amusing. A party was never complete without Dan getting drunk. Then he’d take out his teeth, put his black jacket on back to front and stagger around the room in one of his renowned ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ impressions, an impression I must admit to never having seen better done either before or since. In a strange way Dan seemed to play up to this new mood as if it was the only way he could relate with people. It was as if, having finally emerged into society and finding total acceptance in the role of the clown, he had decided to play the part to the utmost.

Dan Brennan ArtThe charm and the talent was still present in his work, unchanged in the days that he’d work out in his back patio. But at night he’d be at a gallery opening or a party, a figure of friendly fun that everyone could enjoy. It was during this period that his work began to lose its fire, its childlike perfection, as if the very primitive in him was being corrupted by his new role. Although a few of his fantasies were as glorious as ever, many no longer worked. He began painting to order, to other people’s specifications. If someone saw a painting of Dan’s that they liked but which had already been sold, Dan would undertake to do them another just like it. He seemed to be selling more work than ever before, almost becoming a success in a small way. Still he never had any money and I always had the feeling that people were taking advantage of him. Friends taking work and saying they’d pay him as soon as they could. God knows, I was as guilty of this as anyone.

Leo Eaton first came to San Miguel d’Allende in 1969, another starving writer in a town full of starving writers and artists. Dan Brennan died in obscurity at his home in San Miguel in 1989 but his paintings can be found in private collections across Mexico and America.

I’d met my future wife Jeri by this time and gone to live with her in Austin, Texas. We arranged a show in an Austin gallery, Dan and four other artists: ‘The Artists of San Miguel’. It was a financial disaster from which the gallery never recovered but also it was a truly great show. Dan’s paintings, hung in a long gallery all to themselves and properly lit, were overpowering. Students at UT who came to the show, those who loved and understood art, were awed. The Texas art-buying establishment didn’t want to know. Dan sold only two paintings, and then waited months for his money.

Bitterness began to set in. I sensed it when next I visited San Miguel; bitterness against all the people who had been using him. Maybe even a bitterness that came from the realization of what he was losing. Dan started to withdraw from the world again. He was never seen about the streets of San Miguel. He moved to a vast derelict house across the river in the true peasant part of town. Once he came to Austin on a border trip and stayed a weekend with the gallery owner, passive, uncommunicative. He would sit endlessly in front of television, totally withdrawn. He’d visit the gallery when requested but otherwise never left the house. Withdrawal in San Miguel too. I’d ask people who still lived there if anyone had seen Dan. The answer would be “perhaps” or “no, not for a long time”. People still liked him but no one seemed to care any more. The days of Dan the clown had finally drawn to a close.

It’s been almost two years since last I saw Dan. I think all of us did him harm. We accepted him without really trying to understand him. Because he accepted the role of the clown, we used him without realizing the damage that we might be doing to the most precious part of him, his art. For Dan, his art must come from the very simplest basics of life with which he surrounds himself, not from the trappings of a twentieth-century art colony.

It’s been almost two years since last I saw Dan. I think all of us did him harm. We accepted him without really trying to understand him. Because he accepted the role of the clown, we used him without realizing the damage that we might be doing to the most precious part of him, his art. For Dan, his art must come from the very simplest basics of life with which he surrounds himself, not from the trappings of a twentieth-century art colony.

I hope and pray that the damage is not too deep. I cannot and will not believe that the great artist I saw in that shuttered room on Calle Umeran has been destroyed. Rather I feel that Dan has now had his period of social experimentation. It was almost as though, having shut himself away for months at a time, he emerged only to talk through a day and a night before returning again to his own private world. He emerged and for a short period tried to become one of the rest of us. Now I think he realizes yet again that this is not his way. It is possible that Dan is an example of one of the most tragic ironies of the artist. Fame and success will destroy his art just as surely as we were destroying it. It can only survive and grow shut off from the world, safe behind shuttered windows with only the Indian peasants to keep Dan company on his lonely path. Perhaps in the end they are the best people. They don’t judge. They don’t criticize. They don’t demand. They only accept.